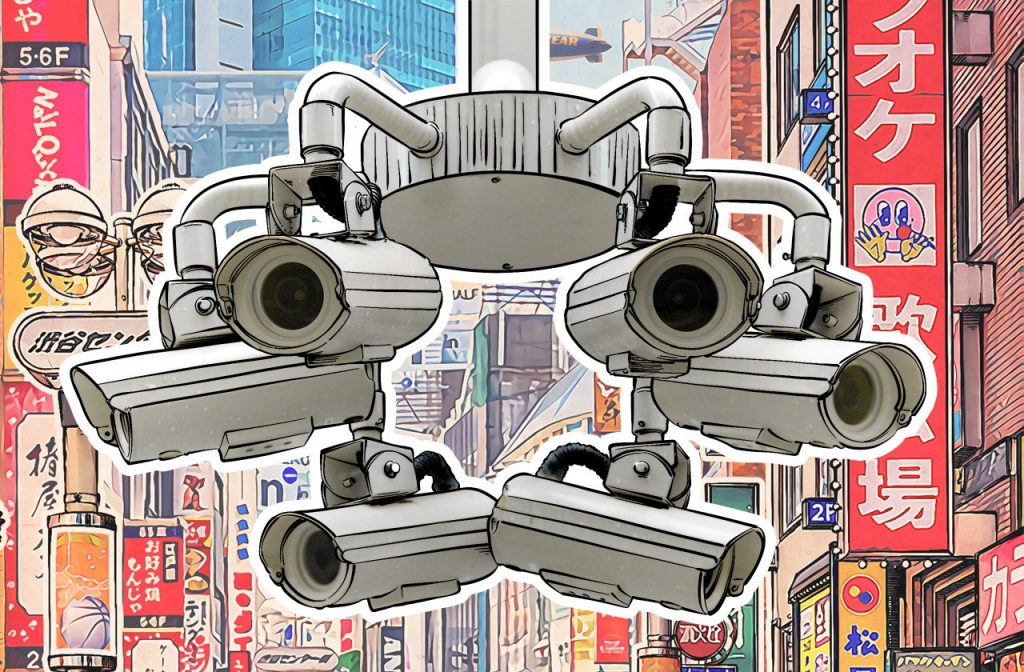

Internet ads are so invasive that we can’t blame you for thinking that Facebook is listening to you talk. It’s probably not, but it is helping ad networks track you across the internet and across your apps. Tech public policy expert Chris Yiu recently tweeted 14 different ways that ads follow you around the internet, even when you’re logged out, in incognito, using a different browser, or on a new device.

One important one is Facebook’s trackers, which are embedded on any site that integrates Facebook “like” buttons, Facebook page widgets, or other social tools:

You open Google and search for a product or website, which helps Google build up a profile of you and your interests. Later on you use your Google account to sign in somewhere else, and you see ads based on this profile (N.B. you can turn ads personalization off if you want to)

![]()

You're logged in to Facebook. You visit a website and it has Facebook's tracking pixel (or Like button) installed, which lets Facebook know you're there. Later on you visit Facebook, and your newsfeed contains adverts based on what you were looking at earlier

Here are a few ways you can minimize unwanted personalization. For example, you can reset your phone’s unique identifier:

You install an app on your phone, and then sign in to it using one of your online accounts. You guessed it: your device ID is now associated with that account. Later on you see ads based on your apps when you're using the account on your computer

N.B. Apple, Android and Windows mobile devices all let you disable or reset your device ID. This won't stop you seeing ads, but it will reduce the amount of personalization that can follow you from one app to another

Unfortunately, you can’t control all tracking—Facebook and Google can collect data on you even if you don’t have an account, by scooping up your friends’ phone contacts or by logging usual browser data. This is the kind of invasive tracking and data collection that prompted the European Union to enact GDPR. So all those “we’ve changed our privacy policy” emails are a good sign—or at least a good start.